Patterns of Revision in The Secret Agent: Conrad as Anarchist

David Mulry, Odessa College

© David Mulry. No part of this text may be reposted or republished without the permission of the author.

[10,700 words]

[Essay first published in The Conradian 26/1 (Spring 2001): 33–59. Reproduced by permission.]

Conrad suggests that in writing The Secret Agent there were times when he was as much an anarchist as some of his characters, describing himself as “an extreme revolutionist” in the preface to the Uniform Edition (xiv). The comment has some truth about it that becomes signally clear in a close examination of his revisions of the text from holograph stage to final publication. A leftist political platform emerges through the revisions in the novel and associates Conrad dramatically with the more strident voices of contemporary radicals like H. G. Wells, the novel’s dedicatee, and R. B. Cunninghame Graham.

The revisions are predictably of various kinds. First, there is a range of stylistic alterations that effect or heighten the work’s impressionistic features, although Conrad himself despised the idea of being labelled an impressionist writer. But the general effect of his changes ties in with the emerging intention of his final version: to make his audience experience, more fully and emphatically, the pathos of his victims, Stevie and Winnie. We have a ready example in Stevie of what such empathy can bring about.

Secondly, the revisions effect major structural changes: an extension of the Assistant Commissioner’s role in Chapter 10; an extended and much revised murder scene (radically changing Winnie’s motivation); and even an altered denouement changing our perception of both the Professor’s and Ossipon’s responses to, and complicity in, the Verlocs’ family tragedy.

The variety of revisions combine to diminish the melodramatic quality in the holograph and serial versions (and which marks much of the “dynamite” fiction of the period), and renders more poignant the social and familial drama played out in the novel. Thus the text is transformed from a sensational magazine story in its earliest drafts into a searching social criticism that engages and paradoxically endorses much in the political platform that Conrad ostensibly condemns elsewhere in the novel, and in some of his private writings, and that much of his contemporary audience generally vilified.

Those stylistic and structural revisions, seen as trends or emerging patterns, embrace, or at least coincide with, a platform of political ideas, and are observable through a number of different states because of the nature of Conrad’s writing process. In the course of this analysis I examine general revision trends that render the book text a more politicized artifact than the serial version. The Secret Agent is a logical choice for such a study because of its subject, the circumstances of its composition, and the availability of primary texts: holograph, serial, and book. The study of the range of revisions in the novel illustrates, at least partly, Curle’s estimate quoted in Gordan’s The Making of a Novelist, that “Conrad’s repeated correction of his work [meant] that ‘some of it is extant in at least six different states – the manuscript, the corrected typescript, the serial form, the American book form, the English book form, and the collected edition book form.’ In addition,” Gordan goes on to say, “Conrad worked on states which, though not extant, can be traced” (1940, 112).

The range of revisions encourages us to make certain assumptions about Conrad’s creative process, and also, where we can examine the mechanical processes of change (in the holograph itself, for example, or between the holograph and serial versions), invites us to track emerging thought processes and designs. The latter are all the more interesting, though more complex, because Conrad’s manner of creation is essentially elliptical, interwoven, and self-reflexive. Certainly by the time Conrad becomes a client of J. B. Pinker (in 1900) a familiar pattern would involve working on holograph and corrected and re-corrected typescript, or what Emily Dalgano refers to as “intermediate typescript,” concurrently (1977, 48).1 Thus Conrad produces a simultaneously emerging holograph text and accompanying typescript as the basis for the serial text. Though the “intermediate typescript” is not available, this process culminates initially in the Ridgway’s serial text, and is presumably followed, at least to a certain extent, in the emerging book text.2

This paper considers the development of The Secret Agent, through some of the significant changes in the holograph manuscript, the serial version, and the book form, from precise textual revisions to sweeping structural shifts. The Secret Agent, between its original conception and its final publication, became a much finer, more polished, and effective statement of Conrad’s ideas, and the precise lines of that development are worth looking into in more detail.

A year later than was first supposed, on 13 February, 1906, Conrad settling down to work in Montpellier, wrote buoyantly to Pinker of his intentions: “As soon as I’ve posted this letter I shall climb up to our tower and sit down to work at the story which is provisionally called Verloc” (CL3 316). In the letters written during work on “Verloc,” among excuses, promises, and accounts of unpaid expenses, Conrad expresses, as usual, concern about his financial position and a commitment to dashing off some short stories as the best and quickest way to raise money. The letters demonstrate that he originally envisaged The Secret Agent as a short story belonging (in its conception and certainly thematically) to A Set of Six,which was eventually published in 1908. It was, for example, written concurrently with Conrad’s final revisions of “Gaspar Ruiz,” begun at the end of 1904; and the two anarchist stories “An Anarchist” and “The Informer” (dated around December 1905), predate it by only a few months as Conrad indicates in a letter to Galsworthy of December, 1905: “I wrote the Anarchist story [“An Anarchist”] and now I am writing another of the sort. I write these stories because they bring more money than the sea papers. ... The anarco story (No 2) is entitled The Informer” (CL3 300). Conrad’s ongoing financial problems are perhaps the most persuasive evidence that he originally intended “Verloc” as a short story. In writing a number of topical stories Conrad was clearly hoping to feed off of the turmoil created in Europe by the Russian Revolution of 1904-5, pandering, one might assume, to the subject’s inherent shock value, but also surely drawn to the rich conflict of ideas and ideologies.

Unlike the other political stories in A Set of Six, that were at least quickly written, in the case of “Verloc,” Conrad faltered. He seemed unwilling or unable to close his work on the story, though he frequently claimed to have the full measure of it. On one occasion, just over a week after the first mention of “Verloc” in the letters to Pinker, Conrad apparently writes with the end in sight:

I’ve also worked at the text of the M of the sea. That and the balance of Verloc you’ll get in the course of a week. ... Don’t imagine that the story’ll be unduly long. It may be longer than the Brute, but not very much so. What has delayed me was just trying to put a short turn into it. I think I’ve got it. (CL3 317)

Perhaps the “short turn” that Conrad had found was the murder of Verloc by his wife and her subsequent suicide. It is, after all, quite different from the press versions and quite a long way removed from the fictions being circulated in the first instance by Nicoll and the Commonweal group and later by the Rossetti sisters. But if Winnie’s story was indeed the “short turn” he needed, something about it seemed to fascinate Conrad, for the end of the story receded rather than approached. His anticipation that “Verloc” would not be much longer than “The Brute” (just over 8,000 words) is a huge underestimation. Gradually, as Conrad’s vision of the story became clearer, it extended.

Instances of spontaneous revision in the holograph, suggest that characters and events slowly came into focus as they were being written as well as being subsequently reconsidered and reshaped. This is significant because it suggests that Conrad was unclear about the drift of his plot as he wrote. At times he stumbles among expressions, trying one after another only to strike each one out and opt for yet another. Along with his determination to have sufficient time to rework the text for its book publication, his early difficulties with expression suggest that Conrad did not completely visualize either the complexities or political ramifications of his narrative until he embarked on the final revision process.

The revisions found at the beginning of Chapter 2, when Verloc is going towards his appointment with Vladimir at the Embassy, offer rich evidence of Conrad’s struggle with the very nature of Verloc, his principal protagonist (at least in the serial version), and with the political ethos of the novel in general. Most revisions here are in the main body of the text rather than marginal or interlinear, indicating trouble with the correct tone as he was writing it rather than in subsequent revision. The corrections represent a gradual upgrading of Verloc’s participation in his immediate surroundings: 3

It was unusually early for him; and his whole person wore an air of early morning freshness. His bluecloth overcoat was unbuttoned, his boots were shiny, his cheeks shaven with a sort of gloss, and even his heavy lidded eyes <looked less sleepy \more refreshed/ than they ever had> <sent out an \a more \than/ usual/ interested glance> sent out glances of positive alertness. Through the park railings these glances beheld \mounted/ men and women <on horseback> \in the Row/, couples cantering past, others advancing sedately ... (Holograph MS 22-3)

Like the later revisions of both Winnie and Stevie, the upgrading of participation here encourages the reader to experience the London morning along with Verloc (actively rather than passively).

At first his eyes are “less sleepy,” which necessarily implies “still a little sleepy.” This is changed to “more refreshed” (an interlinear substitution for “less sleepy”), which is the first indication of a kind of perverse vitality in Verloc, but is still not quite what Conrad is looking for, as, after all, it primarily emphasizes Verloc’s indolence. He takes the characterization still further with the phrase “his heavy lidded eyes sent out an interested glance,” and thus Verloc becomes active rather than passive. Conrad adjusts that description with the interlinear addition “sent out ... a more than usual[ly] interested glance.” This is still not enough, and the final version reflects the need for a more affirmative, and incidentally comically ironic, statement: “his heavy lidded eyes sent out glances of positive alertness.” Thus each stage of revision makes Verloc more actively engaged with his surroundings. The pattern of changes reflects that Conrad was aware of the structural importance of counterbalancing Verloc’s general indolence with his participation in the plot.

Further revisions of the passage clearly occurred between the holograph and serial version, in a draft typescript that has not survived, or in proofs. The serial offers the following description:

It was unusually early for him; and his whole person wore an air of almost dewy freshness. He wore his blue cloth overcoat unbuttoned, his boots were shiny, his cheeks freshly shaven with a sort of gloss, and even his heavy-lidded eyes sent out glances of comparative alertness. Through the park-railings these glances beheld mounted men and women in the Row, couples cantering past ... (Ridgway’s, 6 October 1906, 14)

Conrad brightens the opening with “dewy freshness” compared to the more cumbersome “early-morning freshness” of the holograph, and also once again adjusts the nuance of the final clause, changing “positive alertness” to “comparative alertness.”

At yet another stage of revision, Conrad, always searching as he remarks in The Mirror of the Sea, for the “just expression seizing upon the essential, which is the ambition of the artist in words” (21), effects further changes. The passage runs:

It was unusually early for him; his whole person exhaled the charm of almost dewy freshness; he wore his blue cloth overcoat unbuttoned; his boots were shiny; his cheeks, freshly shaven, had a sort of gloss; and even his heavy-lidded eyes, refreshed by a night of peaceful slumber, sent out glances of comparative alertness. Through the park railings these glances beheld men and women riding in the Row, couples cantering past harmoniously ... (15)

Verloc, rather than “wearing” his freshness, “exhales” it; once again the mood of the passage progressively shifts from the passive, where circumstances act on Verloc, to a point where, for a moment at least, Verloc is engaged, an agent within his environment, or perhaps slightly out of it.

Such revisions, painstakingly emerging in successive attempts at “seeing” his subject truly, are clear indicators of the obscurity that clouds Conrad’s perceptions of the early text, but even here the uncharacteristic lightness of Verloc’s mood (soon to be dashed by the Embassy visit with Vladimir) can be attributed to the influence of the well-to-do London world he seeks to protect. For example, Conrad quickly establishes the complacency of this affluent world through Verloc’s perception of its denizens “riding in the Row” and “cantering harmoniously.” But these apparently bland images are, in fact, loaded, as is demonstrated by the contrast between them and the scene where Stevie is confronted by the broken-down cab driver (discussed in detail below). It would be easy to approve of this world, as Verloc does, were it not for the disturbing sentiments on which it is founded, such as the following chilling credo that appears almost word-for-word in each of the different versions of the text:

Protection is the first necessity of opulence and luxury. They had to be protected; and their horses, carriages, houses, servants had to be protected; and the source of their wealth had to be protected in the heart of the city and the heart of the country; the whole social order favourable to their hygienic idleness had to be protected against the shallow enviousness of unhygienic labour. (15-16)

Verloc’s conviction that the affluent class must be protected is largely unchallenged at the beginning of this tale, though his role (and so, surely, his conviction) is certainly compromised by the end of it. Moreover, many of Conrad’s contemporary readers would have presumably endorsed these sentiments. But even here, at the beginning of the story, there are subtle indications that the narrator does not share Verloc’s “approval.” For instance, in another image that remains unaltered through each stage of the text, Conrad observes: “here and there a victoria with the skin of some wild beast inside and a woman’s face and hat emerging above the folded hood” (15). This disturbingly predatory image is of a piece with Yundt’s subsequent pronouncement that so disturbs the impressionable Stevie: “They are nourishing their greed on the quivering flesh and the warm blood of the people – nothing else” (44). Thus the political implications of Verloc’s conservative view of the social order are played out in the ensuing pages, resulting in a radical alternative. This shift in perspective can be witnessed in the revision process of the text, where some of Conrad’s changes clearly introduce a more politically volatile position.

In her valuable study of the evolution of the text of The Secret Agent, Emily Dalgano observes:

Chapters one, two and three, all written on the same kind of paper, were entitled at various intervals in the manuscript “Verloc.” Chapter four suggests a fresh start. It is entitled “The Agent,” written on larger paper than the rest of the manuscript, and is more heavily corrected than the first three chapters ... A third section of the manuscript has no separate title. In it, chapter numbers have been abandoned, and instructions to the typist about paging [in] the typescript appear regularly. Probably chapters one, two, and three were written in France, four after Conrad had abandoned the original title in April, and the remainder of the novel at Pent Farm with the customary arrangements for typing. (1977, 49)

In their Cambridge Edition of The Secret Agent (1990), Harkness and Reid have further charted the genesis of the tale, although it unfolds more vividly in Conrad’s sometimes histrionic letters. Early letters, for example, suggest, in a tone that veers between mounting panic and resignation, that the short story is running away from him: “Verloc is extending. It’s no good fighting against it. It would take too much time” (CL3 318). In a later letter written (presumably) in mid-March Conrad writes “when the end of Verloc reaches you and also perhaps the first half of the next story we will arrange for our return” (CL3 322). Conrad’s changing sense of his story is reflected in his need for a new title. The original and probably merely provisional title, “Verloc,” could hardly serve for the emerging narrative, and the shift marks the abandonment of the short story framework. Conrad, apparently reluctantly, commits himself to a novel.

Ridgway’s: A Militant Weekly for God and Country began the serialized version of the novel in its 6 October 1906 issue. In a letter dated 12 September to Galsworthy, Conrad writes: “the end is not yet, tho’ 45 thousand words are” (CL3 354). The serial version was a little under two-thirds the size of the novel (at just short of sixty thousand words) with the latter being about eighty-five thousand words. The letter of 12 September suggests that at least another fifteen thousand words remained unfinished with less than a month to the beginning of the American serialization. On 17 (or 19) September in a letter to Pinker, Conrad enclosed: “pp 407 to 428 of Secret Agent – about 2,400 words. Remains to write the half – the dramatic half of the last chapter. I have been at it the best part of last night and am in hopes of pulling it off in a creditable manner” (CL3 358). There is some confusion in this letter as to how far Conrad is from finishing. The holograph manuscript runs to six hundred and twenty-seven pages,4 yet he delivered only as far as page 428 to Pinker, thereby confirming the kind of progress he had outlined to Galsworthy, but not his claims that only “half of the last chapter” remained. A possible explanation would be if Conrad’s references to page numbers were to a corrected typescript, but that is highly unlikely since twenty pages of typescript would run to more than five thousand words rather than two thousand and four hundred.5 A much more likely reason for Conrad’s rather incautious optimism is to be found by looking at the stage he had reached in the narrative at this point. Page 428 of the holograph corresponds to the beginning of Chapter 8 in the book text. The twenty pages submitted to Pinker cover the Assistant Commissioner’s interview with Sir Ethelred and his preparations to attempt to dupe Heat and confront Verloc. Conrad was, indeed, close to finishing, but he was still distracted by the need to flesh out the Verloc family situation and (crucially) to establish cause for Winnie’s pathological response to unfolding events. During that process, control over his material seemed once again to slip away from him.

Chapter 8, of course, involves the extended cab-journey scene and the removal of Winnie’s mother. The sequence was much criticized by his contemporaries for the way it arrests the course of the novel. For instance, an unsigned review of the novel in Country Life (21 September 1907) described the scene as “an excrescence” and “not wanted in the slightest” (in Sherry, 1973, 189). Perhaps the strong reaction was an expression of the frustration and suspense caused by the structural oddity. But as this diversion holds up the reader, so too did it hinder the writer. It had effectively put back an early end to the novel (thankfully, one might add with the benefit of hindsight), as Conrad began to backtrack. Significantly the optimism of his correspondence begins to wane, and it is replaced by a gritty tension arising from the need to produce something worthy and the knowledge that he could not afford to spend too much time:

I am sending you here 17 pp. which is all I can allow to pass out of my hands today. I am sitting night and day over the story, stopping just short of the danger of inducing sleeplessness – for that would be fatal to further production. (CL3 364-5)

Conrad’s evident anxiety is a reflection of the emerging complexity of his subject. Indeed, his treatment of the cab-ride sequence of Chapter 8 (and the intriguing revisions therein) is symptomatic of this developing sense of the story and its implications. The initial depiction of the cab driver, and his subsequent reshaping, offers a range of revisions with pointed political significance (see illustrations 1 and 2). Conrad likens the driver of the cab to Virgil’s Silenus, and his own description and the similarity between the two images hinge at first on a depiction of Bacchanalian excess consistent with the rather disreputable demeanor of the anarchist figures elsewhere in the text:

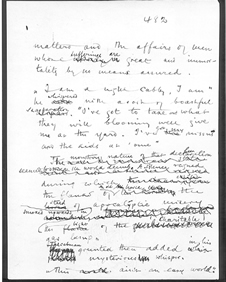

His <vast> \jovial/ purple cheeks bristled with white hairs; and like Virgil’s Silenus <who was talking with> who, <talking> \<discoursing eloquently>/ his face smeared with the juice of berries, <of immortal> \discoursed/ of Olympian Gods to the \innocent/ shepherds of Sicily, he talked <on, \to Steevie/ <the> \this/ obscene Silenus of the gutter> of domestic matters and the affairs of men whose <misery is> \sufferings are/ great and immortality by no means assured. (Holograph MS 481-2)

Conrad’s use of the Silenus figure is much more than a picturesque visual image or a careless classical allusion.6 On the contrary, it is an important component in Conrad’s self-reflexive text.7

On occasion in The Secret Agent, and especially when he is trying to characterize London, Conrad veers towards bold Dickensian sentimentality with the street scenes and the pathos of his childlike Stevie. This is clearly the case in the revisions Conrad made to his presentation of the cab driver, a broadly-drawn, caricatural figure who would not be out of place in Oliver Twist. These revisions are largely successful, driven by fairly subtle shifts and changes. For example, the original holograph reads “his vast purple cheeks,” where “vast” is subsequently deleted and substituted by “jovial” in an interlinear alteration presumably designed to shift the description away from the corpulence attached to, and undermining the credibility of, some of the anarchist clique in the novel and away from the cheeks themselves that graphically paint the cab driver’s ruined alcoholic existence. “Jovial” instead (along with its subliminal reference to Jove, once again exalting the common figure) encourages us to see the cabbie as a beery, hearty, and good-humoured fellow, and makes his subsequent revelation of social inequities all the more disturbing.

The range of revisions in this passage tend to make the cab driver more rather than less credible, so that when “he talked ... to Steevie of domestic matters and the affairs of men whose sufferings are great and immortality by no means assured,”8 his voice resonates with something approaching a simple truth. The sympathetic vision of the night cabby is curious: unlike the anarchists in the novel, he is not scorned, yet he is able to utter secrets about social injustice that inspire much of the subsequent action, resonating first in the actions of Stevie, who carries the bomb, and then in the revenge of Winnie.

The holograph revisions I have been discussing were carried forward into the published novel, even though this entire passage, along with much of the scene, was cut from the serial version without enhancing the episode in any way. In the serial, with several key passages missing, the relationship between the cab driver and Stevie is at best vague. The allusion to Silenus is casual and a little obscure until we read it in the context of the full text, where his song becomes a charged discourse that holds the young shepherd who listens, rapt. Remember that Conrad shows us the Silenus who “discoursed of Olympian Gods to the innocent shepherds of Sicily.” Conrad’s interlinear additions, “discoursed of” and “innocent,” identify a Silenus who, rather than being engaged in song as he is in Virgil, is instead engaged in a more precise, formal, and purposeful address (of which we should perhaps be wary because of Conrad’s systematic treatment of eloquence and formal language), that touches upon arcane knowledge.

By specifying “discourse” and “innocence,” Conrad suggests that Stevie’s innocence is threatened by knowledge. Similarly, the careful phrasing of the cabby’s speech intimates that the broken down figure voices something like truth. His utterance is whispered and secret. Thus, “His strained, extinct voice invested his utterance with a character of vehement secrecy” (128), he speaks in a “mysterious whisper” (129), and, when he turns away with his horse, “‘Come on,’ he whispered secretly” (129). There is an air of secrecy about him just as there is about the Silenus Restaurant where anarchist meetings take place and the Professor tells of his search for the perfect detonator. And perhaps Conrad suggests through analogy that the nature of his secret knowledge, ostensibly nothing more than a glimpse into the everyday “affairs of men,” is not so far from the Silenus who sings of “creation’s birth,” and “of Prometheus tortured by eagles for stealing fire.” His secrets are simple, but nonetheless momentous, and offer perhaps the most incisive condemnation of social inequalities that the novel has to offer:

“I am a night cabby, I am” he <said> \whispered/ with a sort of boastful <despair> \exasperation/. “I’ve got to take out what they will blooming well give me at the yard. I’ve <the> \got my/ missus and the kids at > ’ome” [.]

<It was a monstrous statement; and a silence reigned> \The monstrous nature of that declaration/ seemed to strike the world dumb. A silence reigned during which <the steam \exhaled/ from> the flanks of \the old horse/ <his horse \steed/,> the <horse \steed/> of apocalyptic misery <ascended [illegible]> \smoked upwards in/ the <flame> \light/ of the <illegible> \charitable/ gas lamp. (Holograph 482)

Once again, the passage is deleted from the serial version (possibly by Ridgway’s editors),9 but it is reinstated in the book text with minor changes. For instance, the cabby has a “missus and four kids at ’ome,” and the “declaration” is amended to “the monstrous nature of that declaration of paternity.” The power of the cabby’s seemingly innocuous comment is made much more vivid by the deletion of the initial authorial intrusion. The placement of the passive phrase “a silence reigned” after “the monstrous nature of that declaration seemed to strike the world dumb” leads one to wonder whether, in the Professor’s words, such discourse has sufficient power or the right accent “to move the world.” The apparent disparity between the cabby’s words and their forceful effect signifies the extent and operation of Stevie’s compassionate imagination. The narrator is voicing the shock of disclosure on the innocent Stevie through the figure of the cabby and his broken down horse.

In a telling moment of synchronicity, R. B. Cunninghame Graham picks up a similarly evocative vignette of a London scene in a polemical essay entitled “Set Free”:

A heap of broken harness lay in a pile, and near it on its side a horse with its leg broken by a motor omnibus. His coat was dank with sweat, and his lean sides were raw in places with the harness that he would wear no more. His neck was galled with the wet collar which was thrown upon the pile of harness, its flannel lining stained with the matter of the sores which scarcely healed before work opened them again. The horse’s yellow teeth, which his lips, open in his agony, disclosed, showed that he was old and that his martyrdom was not of yesterday. (1931, 132)

The scene is not without its social implications for Graham who links the fallen horse to the crowd that gathers, as Conrad remarks when he portrays a similar incident in The Secret Agent, “in its quiet enjoyment of the national spectacle” (13). But Graham is more overt in his manipulation of the scene. According to him, the crowd, gathers “gazing at him as he lay, not without sympathy, but dully, as if they too were over-driven in their lives” (133). They watch the fallen work-horse without seeing what the writer sees. They are anaesthetized by work and fail to recognize themselves in the harrowing vision that Graham evokes; not merely of a horse but of the people of a bustling metropolis: “thin, dirty, overworked, castrated, familiar from [their] youth with blows and with ill-treatment, but now about to be set free” (133).

That the two scenes are analogous, is, in itself, startling. Conrad’s establishment voice is hushed and reticent. The episode brims instead with revolutionary rhetoric. Conrad’s revisions show him to be groping for an adequate modifying phrase: “<It was a monstrous statement; and a silence reigned> \The monstrous nature of that declaration/ seemed to strike the world dumb.” Subsequently, though, he turns to the horse, investing it with a significance beyond itself, making it almost mythical in proportion as he plays with the elevated descriptor “steed” and follows it with an evocation of “apocalypse”: “A silence reigned during which <the steam \exhaled/ from> the flanks of \the old horse/ <his horse \steed/,> the <horse> \steed/ of apocalyptic misery.”

While Conrad’s treatment of the scene predates Cunninghame Graham’s piece by five years, it implicitly contains the same revolutionary rhetoric. In his holograph draft Conrad describes the drama of the fallen horses only as a spectacle; in the serial version it has been revised to read “national spectacle.” Conrad was apparently not unaware of the metonymic connection between the image of the horse and labour (or man) in general.10 Nor is Stevie, who shrieks out at the pathos and drama of the fallen horses and is clearly subsequently receptive to the vision of social inequity that the night cabbie offers him. This vision sits uncomfortably with the earlier images (from Verloc’s visit to the Embassy in Chapter 2) of complacent and wealthy people riding “harmoniously” in “the Row.”

It is possible that Conrad’s frame of classical allusion underpins what might be considered a mock-epic treatment – suitable, from a certain perspective, to his stated aim of treating his subject ironically. The epic convention is thus evoked in order to demean further the sordid figures in the novel whose stature could not support such allusive comparisons, like the ornate and rather contemptuous treatment of the beau monde in Pope. The night cabby, however, is elevated rather than undermined by the paucity of comparison. The closing image of him describes the “air of austerity in his departure,” and “the horse’s lean thighs moving with ascetic deliberation” (130). In this moment, before their sordid everyday affairs once again take over, the austere asceticism of the pair elevates the experience to the level of anagnorisis and identifies the night cabby with the ineluctable Professor, whose very austerity makes him a force in the final revision.

Although the novel portrays a divided society, Conrad makes little effort to portray the poverty or suffering that are the reverse side of a critique of opulence. The only extensive study of domestic life in the novel is of the petit bourgeois Verloc family. London’s working classes are shadowy figures, as befits the citizens of the huge dark town Conrad envisaged. Where they are depicted, like the cab-driver, they often take on mythic proportions. When Verloc is walking to the Embassy in the second chapter, according to the holograph version, “A butcher boy driving with the noble recklessness of a circus charioteer dashed round the corner sitting high above a pair of red wheels” (31). While the description “circus charioteer” is perhaps debased in current times with the decline of circus entertainment, the circus was traditionally exciting and glamorous, and, as it stands, the image immediately evokes a vigorous figure (foreshadowing the vigor of Winnie’s unrequited love, the young butcher boy). However in the serial and novel versions, “circus charioteer” is made more precise, becoming “a charioteer in Olympic games” (Ridgway’s 6 October 1906, 63), and “a charioteer at Olympic Games” (17), respectively. The change reinforces that revision reflex that we have seen already, using a classical frame to depict, and thus ennoble, some of the lower class characters.

However, against the potency of Stevie’s compassionate fury, and the night cabby’s simple truths, an alternative of sorts is offered, in the political machinations of Sir Ethelred and Toodles. They are, after all, the binary opposites of the anarchists and the social underclass in the novel. Together these alternatives form the recto and verso of nineteenth-century politics. How far Conrad wishes us to consider the vitality and honesty of the government mechanism in comparison to the anarchists is hard to judge, but the fact that such a comparison exists is largely due to the reshaping of the story’s structure with the inclusion of Chapter 10 in the final revision.

Thus far this essay has focused on minor textual revisions that have redrawn the elements of the text in such as way as to suggest an increasingly politicized perspective. Impressionistic detail has subtly redrawn or redirected narrative sympathies so that the reader is more closely aligned with Stevie’s outraged sensibility than perhaps any other. From very early on, the reader is practically estranged from any sympathy with Verloc. But such delicate revisions, though fascinating and profound, are only part of the story. The broader patterns of change that occur between the holograph and serial texts (which are in essence very similar) and the book text are structural. It is, therefore, to the key structural changes that I shall now turn since, as Harkness and Reid suggest, “In point of fact, the surviving manuscript is not an authorial fair-copy of an essentially completed text but rather a draft of the serial version of the novel” (295).

Tracing Conrad’s process of composition from the holograph one detects a moment of hesitation at the point where he would later insert what is now Chapter 10. The added chapter, detailing the Assistant Commissioner’s pursuit of Verloc, is placed in a pause denoted in the manuscript by a blank line, separating Winnie’s stunned reaction immediately after Heat’s departure from the scene where Verloc must face his wife’s knowledge of Stevie’s death. In the holograph, the circled instruction (perhaps directed to Pinker’s typist) “leave space here” (596) is placed in the gap, indicating that Conrad had, perhaps, already planned the kind of episode needed to give some balance to the end of the story. In any event, the digression is a useful device for heightening the tension of the murder scene by postponing it. But pursuing the Assistant Commissioner’s role in the story also serves to advertise the novel’s frame of reference as wider than the serial, the close of which emphasizes the domestic drama.

Admittedly, the final version relies heavily on the resolution of the Verloc family crisis. The fact is even acknowledged in the added chapter when the Assistant Commissioner, reporting to Sir Ethelred, comments: “from a certain point of view we are here in the presence of a domestic drama” (168). On the surface, that statement appears authentic. Conrad’s comments before and after the book publication can be read as an attempt to suppress the contemporary political content. In a letter to Pinker of 1 June 1907, he expressed his wish to subtitle the novel “A Simple Tale” with the explanation “I don’t want the story to be misunderstood as having any sort of social or polemical intention” (CL3 446). Ostensibly, Conrad’s comment seems to affirm that he does not consider the novel to have any kind of social accountability, but given his stated intention to use an “ironic method,” his remark to Pinker and the subtitle itself become somewhat disingenuous.

Whether intended or not, the inclusion of Chapter 10 works towards the political conclusion (or non-conclusion), and thus this late structural revision shows the developing trend towards rather than away from polemic. The inevitable implication that we draw from the convergence of the familial drama and the political crisis in the revised draft is that they are somehow twinned – essentially metonymic – substituting for, and reinforcing one another.

Chapter 10 begins with the Assistant Commissioner returning to see Sir Ethelred at the House of Commons, and Conrad treads a thin line here between precise delineation of character and lampoon. The Assistant Commissioner is met once again by “the volatile and revolutionary Toodles,” the great man’s private secretary. Both Sir Ethelred and Toodles are described as “revolutionary,” but what that means exactly is another matter. For example, Toodles asks about the success of the Assistant Commissioner’s mission, reflecting that he looked “uncommonly like a man who has made a mess of his job” (162-63). The Assistant Commissioner talks cryptically about his success, until finally he mentions that Toodles has probably met the man who is the final objective of the investigation. Toodles’ incredulous response is highly significant:

Toodles preserved a scandalised and solemn silence, as though he were offended with the Assistant Commissioner for exposing such an unsavoury and disturbing fact. It revolutionized his idea of the Explorers’ Club’s extreme selectness, of its social purity. Toodles was revolutionary only in politics; his social beliefs and personal feelings he wished to preserve unchanged through all the years allotted to him on this earth which, upon the whole, he believed to be a nice place to live on. (164)

Conrad’s description of Toodles’ reaction to the intelligence is riddled with delightful ironies. When we meet Toodles earlier in the chapter he is the “revolutionary Toodles” from the perspective of those vested private interests that oppose nationalization (in the same way that the Lady Patroness is revolutionary). He is described as such because of his association with Sir Ethelred and the “revolutionary” work of nationalizing the fishing industry. Conrad’s use of the word and its subsequent repetition makes it largely redundant, reinforcing a trend that begins much earlier with the portrayal of the anarchists and Verloc. In his own act of nihilism Conrad allows the word to lose its meaning.

Moreover, precisely because it has lost its meaning and is being used in inappropriate ways, “revolutionary” becomes charged with irony. Thus, when Conrad says of Toodles that “it revolutionized his idea of the Explorers’ Club’s extreme selectness, of its social purity,” the reader becomes aware of an ironic comment on the nature of Toodles’ complacent world view. At the same time, Toodles is, from his own perspective, “revolutionized” by the effect the information has had on him.

As Conrad observes when the Assistant Commissioner first meets Toodles, the latter behaves “with the assurance of a nice and privileged child” (105). It is the assurance that falls, for example, to the baby that Verloc and Vladimir see from the Embassy window, where under the watchful eye of a policeman “the gorgeous perambulator of a wealthy baby [was] being wheeled in state across the Square” (24). Implicit in Conrad’s treatment of privilege is a partial criticism of the protection it enjoys. It is only a partial criticism because Conrad embraces the need for order, yet it is a pertinent and sustained criticism in so far as he recognizes that in order to protect privilege, poverty and inequality must exist.

Toodles’ view might have been offered as the dramatic counterpoint to Stevie. They are, after all, very similar: childlike and naive, both act according to the wishes of an older man whom they idolize and both are “revolutionary.” The disparity between their world views becomes systematically more apparent through Conrad’s revisions, and the reader is implicitly invited to judge or weigh the nature and relative value of those experiences: Stevie’s wringing the most out of his limited linguistic range with “Bad world for poor people” (132), and Toodles’ complacent view, deriving from his own privileged experience, of “this earth which, upon the whole, he believed to be a nice place to live on” (164). The latter perspective has neither the raw power of Stevie’s, nor has it the same emotional, moral, or empathic range. Toodles clearly has not experienced life with anything like the intensity of his counterpart.

In addition to the reframing of the two different worlds of The Secret Agent, there is a conscious effort in Conrad’s revisions to reshape his conclusion. In fact, the single most striking element of revision is the altered denouement that changes the ways the reader is invited to see the Professor, Ossipon, and even Winnie.

The depiction of Winnie shifts radically from the holograph text to the book. The process of revision transforms Winnie in the reader’s eyes from being little more than a secondary character to one whose impact upon the plot and themes is significant. The close of the earlier version is a cursory tying up of ends: Winnie commits suicide and Ossipon remains unmoved by the affair. When he pays for the Professor’s drinks with money stolen from Winnie, he does so “negligently” (Holograph 636). The book text, however, shifts its emphasis early on to change the character of Winnie so that she is no longer a melodramatic domestic or sexual victim, but someone who has struck a strange bargain with fate and lost. Henry James asks: “What is character but the determination of incident? What is incident but the illustration of character? What is either a picture or a novel that is not of character?” (1888, 45). The link between character and incident becomes increasingly apparent in Conrad’s revisions.

In the serial and holograph, Winnie (sometimes Minnie) is pictured as a heavy, dull woman, at best unlikely to inspire Verloc with such dour passion (and hardly likely to arouse any interest in Ossipon). The revisions distinctly sexualize Winnie making such aspects of the plot more credible. For instance, her description changes from “young, yet of rounded forms, not very tidy” (6) in the holograph, to “young, yet of rounded form, very tidy about the hair” (6 October 1906, 14) in the serial, to the book version’s: “a young woman with a full bust, in a tight bodice, and with broad hips. Her hair was very tidy” (10).

Having made Winnie more specifically an object of desire, Conrad reworks her character accordingly. Her obsessive maternal relationship, which, in turn, defines her relationship with every other character, is suggested in the earlier versions, but never explored explicitly. An example of this, indicated earlier, is the absence of the butcher-boy episode in the holograph, with all its reverberations of passion, sacrifice, and regret. Other key scenes, like the journey of Winnie’s mother, are reworked and extended. Perhaps the clearest example of the change in Winnie’s character, though, is the murder scene. Little more than a reflexive accident in the earlier versions, it becomes a premeditated act of retribution in the final text. Through revision, Winnie becomes an agent of a revolutionary act that is reinforced by the reiterated, though perhaps ironic, references to her freedom that follow in quick succession: “She had her freedom. … She was a free woman” (189); “Mrs. Verloc, the free woman” (190); and “She was a free woman” (191). Winnie’s freedom translates swiftly into action: “She felt herself to be in an almost preternaturally perfect control of every fibre of her body … the bargain was at an end. She was clear sighted. She had become cunning. … She was unhurried” (196).

In the earlier versions Winnie reacts rather than acts. There is an hysterical impulsion about her response to Verloc’s voice, accentuated by her distance from events and a perspective that makes her merely an observer; she hears “that man’s voice” rather than “her husband’s” (Ridgway’s 15 December 1906, 44). The final version, however, describes her reasoning as “having all the force of insane logic” (192), and in her meticulous actions she savors the tang of retribution: “her wits, no longer disconnected, were working under the control of her will” (196). Winnie in the earlier versions reels back, unthinkingly, like a reflex: “His voice was all that was needed for the absolute sealing of his fate. It went through Mrs. Verloc’s head like a stab” (Ridgway’s 15 December 1906, 45). Fatally, Verloc’s voice is enough in the holograph and serial texts. It drives Winnie to murder; in a few brief moments it is over. She pulls away from Verloc who reaches out for her. Brushing against the table, she knocks the knife onto the floor and scrambles after it, retrieves it and stabs her husband almost before either of them are aware it has happened:

She rose behind the head of the couch muttering. “Shovelled him up.” She stood white, tense, with clenched fists, as she had stood up for Stevie in the old days against the infuriated licensed victualler – her father … Her fists were clenched, but one of them was closed on the yellow bone handle of a carving knife. (Ridgway’s 15 December 1906, 45)

The motivation behind Winnie’s response is ambivalent in the earlier versions: was it an act of premeditated murder, or merely the furious beating of her “clenched fists”? The book text version of the stabbing is quite different, with Winnie palming the knife not reflexively but surreptitiously in preparation for murdering Verloc. There is also a markedly different approach to narrative time between the two scenes. The murder in the earlier versions is a matter of thoughtless, frantic rush, perhaps reflecting the pressures of composition. In the revised version the reader is made aware of the speed of the event occurring on a very different time scale. In fact, the murder of Verloc becomes the closure of a business deal. As the knowledge of her actions possesses her, Mrs. Verloc’s features begin to change not into a reflection of her brother, as in the earlier versions, but into her own look, premeditating and cold: “Her face was no longer stony. Anybody could have noted the subtle change on her features, in the stare of her eyes, giving her a new and startling expression” (196). The close of the novel recreates Winnie anew, briefly, just before she dies. Like Cunninghame Graham’s fallen horse, she is for a moment set free – and in that instant proves herself the most dangerous anarchist of the lot. She repudiates the institution of marriage, commits murder, perverts familial bonds, and takes her own life. In a sense, Winnie once again proves the bleakness of Stevie’s vision and draws the reader with her, not out of prurient interest, but out of sympathy.

The transformation that Winnie undergoes is mirrored in the changes that occur in the Professor who, in the holograph and serial versions, is grotesque rather than terrifying. The pattern of revision in both cases is designed to transform the melodramatic (where the underlying social realism is obscured by sensational excess) into the dramatic. The early characterization of the Professor is markedly similar to the depictions of anarchists by other prominent popular authors of “dynamite” fiction at the turn of the century. His “type” can be found in such works as Stevenson’s The Dynamiter (1885), Chesterton’s The Man Who Was Thursday (1908),and even London’s The Assassination Bureau, publishedposthumously in 1963. The anarchist archetypes that emerge in one text after another are sordid, slightly absurd figures, like the agent of destruction in Wells’s story, “The Stolen Bacillus” (1895).

The comparison with Wells’s anarchist illustrates how far Conrad’s revisions remove the Professor from the clique of frivolous anarchist figures, who, for all their contemporary popularity, are now little more than quaint period grotesques. Wells’s anarchist acts so that:

The world should hear of him at last. All those people who had sneered at him, neglected him, preferred other people to him, found his company undesirable, should consider him at last. Death, death, death! They had always treated him as a man of no importance. All the world had been in a conspiracy to keep him down. He would teach them yet what it is to isolate a man. (151)

The passage could easily have been written in the earlier versions of The Secret Agent. After all, Conrad’s Perfect Anarchist suffers from the same complexes of inferiority and insecurity, presuming some sort of social conspiracy that keeps him down. The Professor, too, is an isolated individual, “miserable and terrible in his loneliness,” as the serial affirms (Ridgway’s 15 December 1906, 47). But the gravity of Wells’s anarchist is not sustained and the high seriousness of his social alienation collapses in the comic peripeteia that closes the tale.

The anarchist in Wells’s story soon discovers that he is being pursued by a bacteriologist (and his wife, Minnie), and breaks the bottle of cholera that he is carrying in the excitement of the chase. Like Conrad’s Perfect Anarchist he chooses to embrace death. Already contaminated, he swallows what is left of the bacteria to move through the city carrying a cholera plague. It is a chilling prospect, but Wells’s story has a comic twist in the denouement, which diminishes the anarchist, as the bacteriologist finally confesses to his wife that the stolen bacteria was not cholera at all but a chemical agent that would turn the anarchist blue. Finally in Wells’s spoof, the civilized city is safe from the threat within (a threat posed melodramatically, but made comically visible and rendered harmless). Most significantly the political frame of the story collapses into the ridiculous.

Conrad’s Professor is similarly trivialized and effectively unmanned at the end of the serial version. The serial closes on a sense of bathos, though there are the beginnings of the terrible significance that will later be evident in the novel: “He looked at no one going up the street to his secret labor, miserable and terrible in his loneliness strolling on deadly like a pest in the street full of men” (Ridgway’s 15 December, 1906, 47). What undermines the role of the Professor in the serial is the corrupting influence of Ossipon’s new-found wealth. Ossipon buys the Professor drinks, while the Professor says: “it is like a contribution to the cause. I must have my relaxation sometimes, and the detonator will cost money” (Holograph 636; Ridgway’s 15 December 1906, 47). The claim that “it is like a contribution” strikes a note of insincerity that associates the Professor with the weaknesses of vice that contaminate the other anarchists, and the act itself implicates him in Ossipon’s sordid crime. In undermining his austere dedication to his task, and in making him share the guilt of Ossipon’s theft and betrayal, the Professor becomes as compromised and as diminished a figure as the other anarchists in Conrad’s sordid coterie.

In the book text, however, the money lies on Ossipon’s hands like a curse (reminiscent, perhaps, of Nostromo’s silver and incidentally heightening the impact of Ossipon’s betrayal of Winnie), and he wants to offload the entire amount, which the Professor accepts in his pragmatic way, yet without touching the money and without becoming contaminated by it. This movement to disassociate the Professor from Ossipon’s baseness begins in the holograph when Conrad describes the Professor’s exit from the Silenus: “He went <out> away up the stairs” (636). Instead of the neutral “he went out,” Conrad specifically notes that “he went away,” a separation that becomes much more explicit through revision:

The incorruptible Professor only smiled. His clothes were all but falling off him, his boots, shapeless with repairs, heavy like lead, let water in at every step. He said:

“I will send you by-and-by a small bill for certain chemicals which I shall order to-morrow. I need them badly. Understood – eh?” (230)

Conrad’s revision works on the association of poverty with integrity for maximum effect. The Professor is all austerity and self-neglect: his interest and passion lie beyond himself. He is properly incorruptible because he will have nothing to do with the legacy and renounces possessions and comfort and desires nothing but the materials for his “work.”

If the serial closes on the compromised figure of the Professor, alienated, aloof, and dwarfed by the proximity of the city, the Professor in the book text is quite different:

the incorruptible Professor walked too, averting his eyes from the odious multitude of mankind. He had no future. He disdained it. He was a force. His thoughts caressed the images of ruin and destruction. He walked frail, insignificant, shabby, miserable – and terrible in the simplicity of his idea calling madness and despair to the regeneration of the world. Nobody looked at him. He passed on unsuspected and deadly, like a pest in the street full of men. (231)

The short emphatic sentences – “He disdained it. He was a force.” – suggest power in the “incorruptible Professor” where the serial suggests impotence and absurdity. This suggestion of power is syntactically reinforced where the mean aspects of the Professor are catalogued and then followed by a caesural pause, effected by a dash that adds tremendous weight to the beginning of the balancing clause “and terrible in the simplicity of his ideas.” The revised text refuses to trivialize the Professor and the threat he poses, unlike the earlier version. If the pest of the serial is a nuisance, in the final version he is a plague.

The pressure mounting during the final weeks, days, and even hours of Conrad’s work on the holograph manuscript continued to build steadily. But even as the final words were rushed through so that they might “leave at noon by rail [so as to be with Pinker by] about 2.40 in time to be typed and catch [the] Southampton mailboat,” the real work was just beginning (CL3 370). After all, there is a considerable difference between the serial and the book texts, and both differ from the holograph version. True, however, to its origins, the serial retains much of the short story about it. Its focus is Verloc and the study of a man foundering, someone who, in Conrad’s words from The Nigger of the “Narcissus,” had not “steered with care” (80). The holograph was severely cut for the serial version. Later revision shows evidence of a profound rethinking of plot and character and considerable rewriting and additions to effect a much more sensitive and especially politically sensitive vision. However, the political dimensions of this tale are framed, and indeed given substance, by the domestic arena, which is perhaps one of the reasons that the novel continues to claim an audience while so many sensational or overtly polemical texts from the same period have fallen away.

If Conrad’s novel was ever out of control, it was not an indication of the structural awkwardness that critics have observed in Lord Jim and which Conrad later commented on in his “Author’s Note” to that volume (vii). Nor can it be traced to the helpless equivocation of the inexperienced author of An Outcast of the Islands, who declared: “all my work is produced unconsciously (so to speak) and I cannot meddle to any purpose with what is within myself – I am sure you understand what I mean – It isn’t in me to improve what has got itself written” (CL1 246-47). In the mature Conrad, such early equivocation gives way to a profound engagement with revision and, through revision, the conviction that his subject may be fully revealed:

The proofs of Sect. Agt will be given back end June not before. You know my dear Pinker that I wish to do my best but I cannot do better. I must see that story. The mere notion of you sending the proofs to Harpers puts me in a fever of apprehension. Don’t do it for goodness’s sake. You know it was always understood the book had to worked upon thoroughly. (CL3 433)

Conrad’s compromises in the serial version of the text, and his subsequent conviction that the book text must evolve and become a different story, are clearly implied in his “fever of apprehension” that his publisher might set the novel as it then stood. Those concerns are repeated in a subsequent letter to Pinker, dated 18 May 1907, even as the revision process draws to a close:

The proofs of S.A.have reached me and I have almost cried at the sight. I thought that I was to have galley slips for my corrections. Instead of that I get the proofs of set pages! Apart from the cost of correction which will be greatly augmented through that there is the material difficulty of correcting clearly and easily on small margins. (CL3 439)

Conrad’s revisions are indicative of the close, compulsive attention of an “enthusiast.” When, in “A Familiar Preface” to A Personal Record, he writes “Give me the right word and the right accent and I will move the world” (xiv), he is voicing a revolutionary credo. It is hardly surprising, then, when the artist identifies himself closely with one of his own most extreme creations, the Professor, of whom he comments (in a letter to Cunninghame Graham dated 7 October 1907): “in making him say ‘madness and despair – give me that for a lever and I will move the world’ I wanted to give him a note of perfect sincerity. At the worst he is a megalomaniac of an extreme type. And every extremist is respectable” (CL3 491). It is significant, however, that the revised and rewritten end of the book text shows us Ossipon, horribly fascinated by the journalistic phrases, describing Winnie’s suicide as “This act of madness or despair” (231). It is the lever of which the Professor speaks, but Conrad has his hands upon it too, and the closing lines of the book text offer us a potent vision of narrative as detonator and a writer “terrible in the simplicity of his idea calling madness and despair to the regeneration of the world” (231).

The progress of Conrad as an artist is reflected in the variety of revisions that reshape The Secret Agent. As his redrafting of the novel demonstrates, he is no longer the naïve writer who could proclaim: “It isn’t in me to improve what has got itself written” (CL1 247). In particular, such a comment fails to account for the painstaking process of revision whereby we see, suddenly laid bare, the workings that reveal the subtle metonymy of anarchist and artist.

Endnotes

1. Gordan remarks how in the case of the early fiction “the six states mentioned by Curle cannot all be followed for any important story, either because the story never existed in all six or because some have been lost” (112).↩

2. As the Cambridge Edition of The Secret Agent points out, there are four “text documents” available via which the course of the novel may be charted: the holograph, the serial version published in Ridgway’s magazine, and the first editions published in the U.K. and the U.S. (236). The intermediary stages of the text, though missing, are generally clearly implied in the range of revisions that exist between holograph, serial and first editions and Conrad’s own acknowledged practice such as when he writes to Pinker about Nostromo, “of the other half of the book a lot is done, written actually on paper; though not fit to be shown even to you. In fact it is not typed yet. My wife had bad neuralgia (we suppose) in the right hand and it has delayed the completion of even this part: for as you know I work a lot upon the type” (CL3 55). While Conrad was no longer relying upon his wife’s secretarial skills during the period in which he composed The Secret Agent, the principle of working “a lot upon the type” is sustained.↩

3. Here and elsewhere in this paper the following editorial conventions are used to indicate revisions to the holograph manuscript: interlinear insertions are indicated by slashes – \ / – and deletions by angled brackets: < >.↩

4. The holograph actually runs to page 637, but this is because of a mistake in the numbering, with pages running to 433, then 444, 445, etc. There is no indication that ten pages are actually unaccounted for as the text is unbroken. The mistake is simply carried forward.↩

5. Even Conrad’s estimation is generous. The holograph pages in this section range from around 60 (58 on page 407), to around 120 (115 on page 414) words per page, depending on variables such as dialogue and the amount of correction or deletion. An average of 90 words per page gives a total of just under 1900 words for the batch. It is likely that Conrad over-estimated to reassure Pinker that the writing process was running smoothly.↩

6. Notably, the range of classical allusion spreads elsewhere in the novel where Verloc is likened to the journeying Odysseus and Winnie is compared to Penelope. When Verloc returns from the Continent in Chapter 9, Winnie is described as talking at Verloc “the wifely talk, as artfully adapted, no doubt, to the circumstances of this return as the talk of Penelope to the return of the wandering Odysseus” (139). The coincidences and parallels multiply as the allusions are explored, indicating the pervasiveness of the allusive frame. The anarchist clique is roughly equivalent in moral terms, at least, to Penelope’s suitors though only Ossipon becomes an actual suitor to Winnie.↩

7. Earlier during Verloc’s interview with Vladimir, Vladimir asks Verloc: “You haven’t ever studied Latin – have you?” His answer is surly and aggressive: “’No,’ growled Mr. Verloc. ‘You did not expect me to know it. I belong to the million. Who knows Latin? Only a few hundred imbeciles who aren’t fit to take care of themselves’” (24). During Verloc’s encounter with Vladimir, the authorial voice is sympathetic towards Verloc. Yet despite Verloc’s contempt of Latin and the cultural and class barriers it signifies, the authorial voice suggests familiarity with Latin texts, and it does so without compromising its sympathetic position. It is the subtle diffusion of sympathy and opposition that makes Conrad’s position both provocative and elusive. Significantly the authorial voice can sympathize out of its class.↩

8. This alternative spelling of Stevie is used extensively, then irregularly in the Holograph, as is the alternative, Minnie, for Winnie Verloc.↩

9. Conrad indicated in a note to Pinker that he assumed Ridgway’s might wish to edit the wordier passages of the text and apparently marked segments to excise where he thought appropriate. Harkness and Reid rightly note that his comments to Pinker probably post-date the typesetting for Ridgway’s early issues, and hence Conrad’s muted rage at the “rag” and their editors after receiving the first instalments. Dalgano even suggests that Conrad “attempted a style which could be simply dismantled to suit the requirements of a magazine” (54), though such an idea, while attractive and even persuasive, fails to take into account the atmosphere of crisis that surrounded much of the later composition.↩

10. Epstein persuasively examines this particular scene as a derivative of Anatole France’s short story “Crainquebille” (1992, 191).↩

Works Cited

Conrad, Joseph. The Secret Agent. Holograph Manuscript (1906). Philadelphia: Rosenbach Museum and Library.

-----. “The Secret Agent.” Ridgway’s: A Militant Weekly for God and Country. New York: 6 October - 15 December, 1906.

Dalgarno, Emily K. “Conrad, Pinker, and the writing of The Secret Agent.” Conradiana 9 (1977): 47-58.

Epstein, Hugh. “A Pier-Glass in the Cavern: The Construction of London in The Secret Agent.” In Conrad’s Cities, edited by Gene M. Moore. Amsterdam: Rodopi 1992.

Gordan, John Dozier. Joseph Conrad: The Making of a Novelist. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1940.

Graham, R. B. Cunninghame. “Set Free.” In Selected Modern English Essays, edited by H. S. Milford. Oxford: Oxford University Press 1931.

James, Henry. “The Art of Fiction.” In Partial Portraits. London and New York: Macmillan, 1888.

Karl, Frederick R. The Three Lives. London: Faber 1979.

Miller, David. Anarchism. London: Dent and Sons 1984.

Sherry, Norman, ed. Conrad: The Critical Heritage. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1973.

Virgil. The Eclogues, Georgics and Aeneid of Virgil. Translated by C. Day Lewis. Oxford: Oxford University Press 1966.

Wells, H. G. Selected Short Stories of H. G. Wells. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1964.