Lookalikes: Conrad and the Denial of Human Individuality

Jeremy Hawthorn,Norwegian University of Science and Technology

jeremy.hawthorn@hf.ntnu.no

© Jeremy Hawthorn. No part of this text may be reposted or republished without the permission of the author.

It is well-known that the first American book edition of The Nigger of the ‘Narcissus’, published 30 November 1897, was retitled The Children of the Sea: A Tale of the Forecastle for the American market. But the American periodical edition of Joseph Conrad’s novella had already been published between August 8 and September 12 of the same year in the Illustrated Buffalo Express, under its original title of The Nigger of the Narcissus: A Tale of the Forecastle (lacking quotation marks around ‘Narcissus’), and with a number of striking line drawings by an unidentified illustrator named ‘G.Y.K.’—possibly G. Y. Kauffmann, art director of the Bachellor newspaper syndicate—and that seem not to have been reproduced elsewhere (see figures 1-3).

The Illustrated Buffalo Express (Figure 4) was a very different sort of periodical from the New Review,the journal in which The Nigger of the ‘Narcissus’ was first published in Britain. Peter McDonald has confirmed that publication in the New Review was extremely important for Conrad because of the prestige of the journal and the literary status that association with it would bring him. Although Conrad was always concerned with the economics of publication—he was more or less constantly in debt and continually living beyond his means even when his means became, in later years, substantial—his desire to be published in the New Review had other motives behind it than financial ones. The New Review’s editor W. E. Henley (1849-1903) was, as McDonald writes, ‘a commanding presence on the British literary scene in the mid-1890s.’1

Association with the New Review would bring Conrad cultural rather than economic capital, and as McDonald shows, Conrad had the journal in mind for The Nigger of the ‘Narcissus’while he was still writing the work. The politics of the journal were, like those of another periodical associated with Henley, The National Observer, ’Tory and imperialist’ as McDonald observes.2 The reactionary views of the Henley circle ranged from the traditional through the ludicrous to the offensive: McDonald quotes from an unsigned article entitled ‘Anti-Woman’ that was published in The National Observer in 1892 that explained sentimentality as ‘the result of centuries of retarded evolution’ that was still manifest in the behaviour of ‘Celts’ (possibly a euphemism for ‘Irish’), ‘negroes,’ and ‘women.’3 The reactionary aspects of Conrad’s novella (anti ‘sentimentality,’ anti trade unionist, pro hierarchy, and at times undeniably racist) would have gone down well with Henley and his circle and, as McDonald demonstrates, were intended to do so.

The Illustrated Buffalo Express was clearly another kettle of fish altogether. While the New Review was a national periodical the Illustrated Buffalo Express had a much more obviously provincial identity, with many articles and illustrations relating to the region. It clearly aimed at a more general educated and informed readership, whilst the New Review was elitist, cliquish, and exclusive. The ‘literary’ content of the Express was in no way cordoned off from the very many commercial advertisements that filled—cluttered up—its pages. And it was indeed quite generously ‘illustrated’—something that distinguished it from the New Review in a cultural as much as a technical sense.          Â

Thanks to the Conrad First website, this serialization can now be examined by scholars online. Thanks, too, to the eagle eye of Alan Donovan I am now aware that the opening page of the first installment that appears in the issue for August 8, carries a striking advertisement for Chas. F. Doll’s furniture store (Figure 5).

In an article entitled ‘The Use of “Coon” in Conrad: British Slang or Racist Slur?’4 I argued that editors had frequently mis-characterized Conrad’s use of the slang term ‘coon’ as racist. My case was that in at least three cases, involving The Nigger of the ‘Narcissus,’ the short story ‘To-Morrow,’ and Chance (1913-14), it made no sense to confer a racist meaning on the term as in each case the word was applied to a white man. As a term of British slang ‘coon’ may have no racist associations, although the racist meaning it has in American slang usage makes such a non-racist meaning less likely today than it was in Conrad’s time. In my article I conceded that two further examples, one in Lord Jim (1900) and one in a letter of Conrad’s, might involve a racist meaning but in my opinion probably did not.

So far as the advertisement in the Illustrated Buffalo Express is concerned, however, there is really no doubt that the term is thoroughly racist, ‘coon’ here signifying an African-American.5 The racist implication is that whereas White people are each and every one possessed of recognizable marks of individuality, Black people are indistinguishable one from another. The sentiment is a common racist assumption or slur, and its force varies between the assertion that all Black people (or Chinese, or Indian, or Malayan, or whatever) are the same, and the equally offensive implication that they can be treated as if they are the same even if they are not.

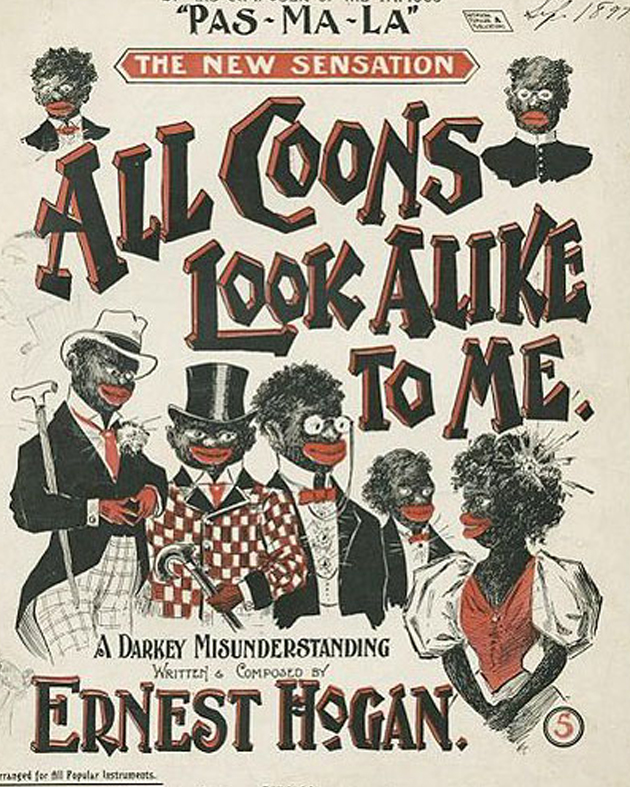

‘All Coons Look Alike to Me’ (Figure 6) was a song that was first published in this form in 1896 and immediately achieved great popularity:

Sheet music, late 1890s.

Click here to listen to a 1902 recording

Talk about a coon a having trouble

I think I have enough of ma own

It’s alla bout ma Lucy Jane Stubbles

And she has caused my heart to mourn

Thar’s another coon barber from Virginia

In soci’ty he’s the leader of the day

And now ma honey gal is gwine to quit me

Yes she’s gone and drove this coon away

She’d no excuse to turn me loose

I’ve been abused, I’m all confused

Cause these words she did say

Chorus

All coons look alike to me

I’ve got another beau, you see

And he’s just as good to me as you, nig!

Ever tried to be

He spends his money free,

I know we can’t agree

So I don’t like you no how

All coons look alike to me

Never said a word to hurt her feelings

I always bou’t her presents by the score

And now my brain with sorrow am a reeling

Cause she won’t accept them any more

If I treated her wrong she may have loved me

Like all the rest she’s gone and let me down

If I’m lucky I’m a gwine to catch my policy

And win my sweet thing way from town

For I’m worried, yes, I’m desp’rate

I’ve been Jonahed, and I’ll get dang’rous

If these words she says to me [repeat chorus]

The big surprise for a modern reader is that this racist song was actually written by an African-American. According to Dave Wondrich:

‘All Coons’ was written by one Ernest Hogan, and his Vaudeville tag was ‘The Unbleached American’ (his real name was Reuben Crowders; ‘Hogan’ was either an attempt to butter up the notoriously negrophobic Irish or a sly jibe at them—or both). He was a black man from Bowling Green, Kentucky; as with every other American institution, blackface minstrelsy was a lot more complicated than it seems at first glance: wipe off that cork and you never knew whom you’d find. Hogan had a handful of hits, but none as big as ‘All Coons.’ Which brings us to problem two: Hogan sort of, slightly, a little bit stole the song. What he did here was take a particularly catchy Chicago barroom ditty, clean up the words (as he thought) and tack on a verse setting up the situation of a certain young lady who is equally indifferent to all other suitors now that she has a new beau. The ‘coons’ of the title and chorus, went his reasoning, was an improvement over the original ‘pimps.’ ‘All pimps look alike to me’—in the era of the ho and the byotch, inoffensive and almost sweet; back in the days, unprintable. ‘Coons’ and ‘nigger,’ however, could flit through the mouths of the striving classes without provoking intake of breath or slantendicular glance.6

The ironies of an allusion to this song appearing on the same page of the Illustrated Buffalo Express on which Conrad’s The Nigger of the ‘Narcissus’ opens are considerable. While the song reassures readers in comic mode that Black people are not possessed of any distinguishable individuality, the advertisement suggests that even furniture that looks the same can have hidden differences.7 Amongst other crew members of the ‘Narcissus’ James Wait and Donkin stand out as ‘different,’ but different in a bad sense.

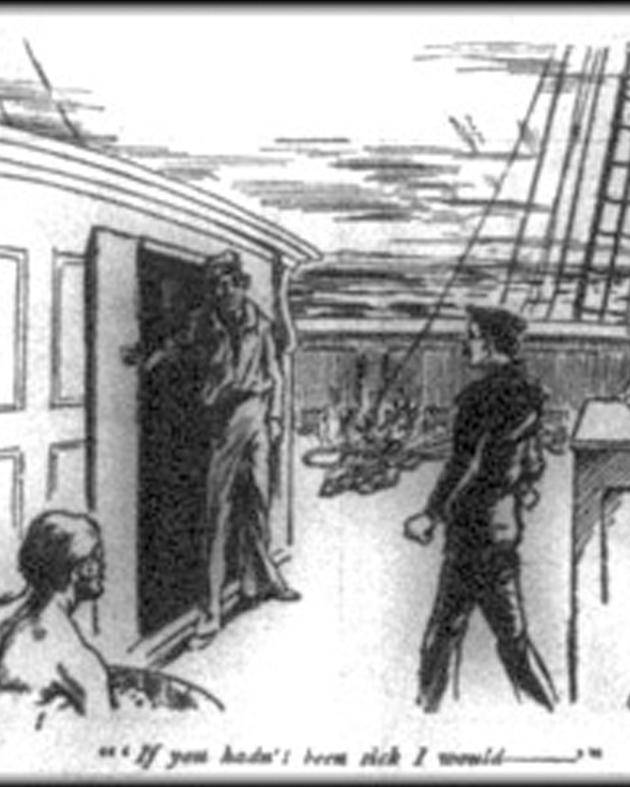

Interestingly, the first illustration accompanying the serialized novella in the Illustrated Buffalo Express shows James Wait from the back, his face half hidden, being stared at by the crew of the ship (see figure 7). It is a most striking depiction, with the rest of the crew all bathed in light from a lantern held aloft by a sailor and arranged in a semi-circle around the dark figure of Wait, who towers above them all. Looking up at him too, and also sharing his darkness although his face is visible, is the figure of the mate (he is clutching what is presumably the sheet of paper from which he has been reading the names of the crew). The illustration is captioned ‘“My name is Wait—James Wait.”‘

The illustration combines, then, the fascination that the figure of ‘the Negro’ holds for those White readers who can be comforted by the thought that all ‘coons’ look alike, with that most telling of marks of individuality: a personal name. But although James Wait has a name, in the illustration he does not have more than a hint of a face. In most of the subsequent illustrations accompanying the text of the novella (see figures 8-11) Wait is at least partially obscured or depicted from behind.

Like the rest of the crew the readers of the Illustrated Buffalo Express were presumably meant to be paradoxically fascinated by the figure of a man who, if we are to believe the text of the advertisement, looked just like all other Black people. Like the readers of the periodical, perhaps, the crew are both fearful and curious when faced by a ‘Negro,’ half sure that they know that ‘all coons are the same,’ but half fearful that perhaps they are not. A couple of years later on in his career, in Heart of Darkness (1899) Conrad was to have his framed narrator Marlow express some comparable feelings about the Africans he could hear but not see from his river steamer.

The earth seemed unearthly. We are accustomed to look upon the shackled form of a conquered monster, but there—there you could look at a thing monstrous and free. It was unearthly, and the men were—no, they were not inhuman. Well, you know, that was the worst of it—this suspicion of their not being inhuman. It would come slowly to one. They howled and leaped, and spun, and made horrid faces; but what thrilled you was just the thought of their humanity—like yours—the thought of your remote kinship with this wild and passionate uproar.8

As Captain Allistoun says of James Wait in The Nigger of the ‘Narcissus’—’He might have been half a man once’9—an admission that bespeaks a partial recognition of his own thought of Wait’s humanity and of his kinship with him.

Given all this, it is ironic that Conrad is remarkably consistent in his fiction in presenting with scorn and contempt those who use formulations of the ‘all x are alike’ variety.

When characters in Conrad’s fiction make a claim that all people of a particular ethnic group look the same, for example, Conrad typically confounds his (White) readers’ expectations and gives the sentiment to a non-White person who applies it to White people. Here are some examples from early in Conrad’s writing career:

‘Ada! I come soon,’ answered Ali from the doorway in an offended tone, looking back over his shoulder. . . . How could he clear the table and hang the hammock at the same time. Ya-wa! Those white men were all alike. Wanted everything at once. Like children . . .10 (An Outcast of the Islands, 1896, ellipses in original)

It was not the man—those Dutchmen are all alike.11 (‘Karain: A Memory’, 1897)

This was simple prudence, white men being so much alike at a distance that he could not tell who I might be.12 (Heart of Darkness, 1899)

The two whites had a liking for that old and incomprehensible creature, and called him Father Gobila. Gobila’s manner was paternal, and he seemed really to love all white men. They all appeared to him very young, indistinguishably alike (except for stature), and he knew that they were all brothers, and also immortal.13 (‘An Outpost of Progress’, 1897)

It is surely impossible to believe that Conrad was not, by means of such examples as these, mocking a particular sort of racist insularity that assumed that ‘we’ are all distinguishable individuals and ‘they’ are all the same. In these short passages Conrad makes his White readers feel what it is like to be on the receiving end of a gaze that dissolves out their individuality and thus their humanity. The example from Conrad’s second novel An Outcast of the Islands, moreover, adds to the characterization of white men the allegation that they are like children—one of the most frequent components of White racist abuse of non-White people.

Such a reversal of stereotypes should not be unexpected from the author who surprised the first readers of Heart of Darkness by having the framed narrator, Marlow, tell his listeners that ‘this also ... has been one of the dark places of the earth’—referring not as they, and as the first readers of Heart of Darkness might have expected, to ‘darkest Africa’—but to London and to England.

To see a group of human beings as ‘all alike’ is to deny that its members are possessed of that characteristic that defines a modern sense of the human: individuality. The first (or according to some accounts, second) short story written by Conrad, ‘The Idiots,’ composed while he was on his honeymoon on the coast of Brittany in 1896, explores the extent to which individuality and uniqueness are necessary components of our sense of the human. When the father in this story, Jean-Pierre, thinks of his (at that stage) three retarded children, he uses a similar formulation: ‘Three! All alike! Why? Such things did not happen to everybody—to nobody he ever heard of. One yet—it might pass. But three! All three.’14 His inability or unwillingness to search out particularities, defining uniquenesses, in his children, exposes a limitation in his own humanity.

That such an attitude borders on what we can now more easily recognize as a sort of fascist thinking is apparent in the following extract from the futuristic fantasy cum political satire The Inheritors (1901) which Conrad co-authored with Ford Madox Hueffer (later Ford Madox Ford):

It was impossible to walk, impossible to do more than tread on one’s own toes; one was almost blinded by the constant passing of faces. It was like being in a wheat-field with one’s eyes on a level with the indistinguishable ears. One was alone in one’s intense contempt for all these faces, all these contented faces; one towered intellectually above them; one towered into regions of rarefaction.15

In Conrad’s longest and, by many accounts, greatest novel Nostromo (1904), a slightly different sort of example helps the reader to recognize the limits of Mrs Gould’s acceptance of the humanity of the Indians who work the mine. Of Don Pepe, we learn that

Even when the number of the miners alone rose to over six hundred he seemed to know each of them individually, all the innumerable Jos’s, Manuels, Ignacios, from the villages primero—segundo—or tercero (there were three mining villages) under his government. He could distinguish them not only by their flat, joyless faces, which to Mrs. Gould looked all alike, as if run into the same ancestral mould of suffering and patience, but apparently also by the infinitely graduated shades of reddish-brown, of blackish-brown, of coppery-brown backs, as the two shifts, stripped to linen drawers and leather skull-caps, mingled together with a confusion of naked limbs, of shouldered picks, swinging lamps, in a great shuffle of sandalled feet on the open plateau before the entrance of the main tunnel.16

But the same novel shows Conrad extending his use of the formulation to criticize not an attitude towards a racial or ethnic group, but a view of a socio-economic class as his character Nostromo (the Capataz) treats the rich as indistinguishable:

‘Por Dios!’ said the Capataz, passionately. ‘You fine people are all alike. All dangerous. All betrayers of the poor who are your dogs.’

‘Ah! you are all alike, you fine men of intelligence. All you are fit for is to betray men of the people into undertaking deadly risks for objects that you are not even sure about.’17

There are two further examples of Nostromo’s inability to detect the individuality of the rich following his political rebirth after the swim back from the hidden treasure.

How are we to interpret such statements? Given Conrad’s consistency in using the ‘all x are the same’ formulation implicitly to criticize racial stereotyping, there is a strong case to argue that Nostromo’s utterances about the rich are meant to betoken not revolutionary political insight but self-serving prejudice. If modern left-leaning readers are tempted to feel that Nostromo gets it right here, they may need to consider that this is not how Conrad would have seen the matter.

Indeed, those readers who approved of such sentiments at the time the novel was first published may equally well have been nostalgic paternalist Tories or sympathisers with the views of W. E. Henley that I mention above. It is worth noting that the second of the two quotations citing Nostromo’s contempt for the rich comes when he is dissuading Dr Monygham from reporting that the treasure is hidden where, unbeknownst to Monygham, it actually is hidden—on the Great Isabel. When Nostromo talks about fine men of intelligence being fit only to betray men of the people, he is speaking in bad faith and as a man who is himself planning to become rich and to separate himself from the common people.

After race and class, there is gender; Conrad’s use of the ‘all x are the same’ formulation seems to proceed through these well-defined categories in order. In Under Western Eyes (1911) the exiled Russian revolutionary Sophia Antonovna exclaims to Razumov, who she believes to be a fellow conspirator and successful terrorist: ‘You men are all alike. You mistake luck for merit. You do it in good faith too! I would not be too hard on you. It’s masculine nature. You men are ridiculously pitiful in your aptitude to cherish childish illusions down to the very grave.’18 Her tone is, it should be said, ironic and teasing rather than wholly serious.

But in Chance, the novel following Under Western Eyes, a similar opinion more seriously expressed is attributed both to the framed narrator Marlow and to the minor character Mr Fyne. When the unsympathetic and ‘feminist’ Mrs Fyne appeals to Marlow for help, his response is to see her appeal as based on something typically female.

And indeed that Mrs. Fyne should have appealed to me at all was in itself the evidence of her profound distress. ‘By Jove she’s desperate too,’ I thought. This discovery was followed by a movement of instinctive shrinking from this unreasonable and unmasculine affair. They were all alike, with their supreme interest aroused only by fighting with each other about some man: a lover, a son, a brother.19

Marlow’s inability to find marks of particularity in women is mirrored in part by Mrs Fyne’s husband:

The girl-friend problem exercised me greatly. How and where the Fynes got all these pretty creatures to come and stay with them I can’t imagine. I had at first the wild suspicion that they were obtained to amuse Fyne. But I soon discovered that he could hardly tell one from the other, though obviously their presence met with his solemn approval.20

Finally, in Victory (1915), Conrad manages by means of a poisonous outburst from the satanic, murderous, and (it is strongly implied) homosexual Mr Jones to merge class and gender prejudice:

Mr Jones was biting his lower lip, in a deep meditation. It was only towards the last that he looked at Heyst.

‘Unarmed, eh?’ Then he burst out violently: ‘I tell you, a gentleman is no match for the common herd. And yet one must make use of them. Unarmed, eh? And I suppose that creature is of the commonest sort. You could hardly have got her out of a drawing-room. Though they’re all alike, for that matter. Unarmed! It’s a pity. I am in much greater danger than you are or were—or I am much mistaken. But I am not—I know my man!’21

From what I have written so far, then, it would appear that with the exception of his depiction of James Wait in The Nigger of the ‘Narcissus’ Conrad is consistently on the side of the angels, opposing the views of those who, on the basis of racist, socio-economic, or gender prejudices deny the humanity of a group to which they do not belong. But it has to be conceded that Conrad’s record on such matters is not unblemished. The best-known attack on Conrad for his alleged racism was mounted by the Nigerian novelist and critic Chinua Achebe. In a lecture delivered in the United States in 1975 and frequently published subsequent to its original delivery, Achebe focused upon Conrad’s depiction of Africans in Heart of Darkness and accused him of being a ‘bloody racist’ (a formulation that was somewhat softened when a revised version of the lecture was published in print).

Without entering into the arguments about the racism that Achebe alleged against Heart of Darkness one can note that the readers of the Illustrated Buffalo Express in the summer of 1897 had access in its pages to what is probably the work of Conrad’s that is most vulnerable to the charge of racism. Although the portrayal of James Wait is not consistently racist, and although as various commentators have pointed out the most overtly racist comments expressed by a character in the work are uttered by the White Donkin, who is treated with contempt by the narrative, the narrator also characterizes James Wait in ways that are racist and that deny his humanity. It is interesting that a word used in the passage I quote from ‘An Outpost of Progress’ by Gobila about white men—’indistinguishable’—is in the longer work applied to James Wait.

The lamplight lit up the man’s body. He was tall. His head was away up in the shadows of lifeboats that stood on skids above the deck. The whites of his eyes and his teeth gleamed distinctly, but the face was indistinguishable. His hands were big and seemed gloved.22

In Lord Jim the framed narrator Marlow says of Jim that ‘I am fated never to see him clearly.’23 If Marlow is fated never to see Jim clearly, the narrator and reader of The Nigger of the ‘Narcissus’ are fated never to see the individual James Wait clearly. His face is either indistinguishable or it is a mask and his hands are as if gloved.24 The illustrator of the novella in the Illustrated Buffalo Express captured something crucial to Conrad’s presentation of James Wait in his or her pictures: James wait is much looked at but never clearly seen. Readers of The Nigger of the ‘Narcissus’ (and viewers of the illustrations in the Illustrated Buffalo Express) are encouraged to look at James Wait, but are never allowed to see him clearly.

When in his Preface to the work Conrad claims that his aim is to make the reader see, it has to be said that so far as the humanity of the novella’s eponymous hero is concerned, this is an aim that is never more than partially realized.

Illustrations

Figure 1.↩

Figure 1.↩

Figure 2. Wright’s.↩

Figure 2. Wright’s.↩

Figure 4.↩

Figure 4.↩

Figure 5.↩

Figure 5.↩

Figure 6. Hewitt’s.↩

Figure 6. Hewitt’s.↩

Figure 7.↩

Figure 7.↩

Figure 8.↩

Figure 8.↩

Figure 9.↩

Figure 9.↩

Figure 10.↩

Figure 10.↩

Figure 11.↩

Figure 11.↩

Endnotes

1. Peter McDonald, 'Men of Letters and Children of the Sea: Conrad and the Henley Circle Revisited,' The Conradian 21(1), Spring 1996, 22.↩

2. McDonald, 23. ↩

3. McDonald, 33, quoting from The National Observer of 7 May 1892, 633.↩

4. Jeremy Hawthorn, 'The Use of "Coon" in Conrad: British Slang or Racist Slur?,' The Conradian 30(1), 2005, 111-17.↩

5. For the origins of this slur, see Hawthorn, "The Use of "Coon" in Conrad.'↩

6. Source: Dave Wondrich, 'The First Rock 'n Roll Record'. A short film titled All Coons Look Alike to Me was released by the Warwick Trading Company in 1909.↩

7. Henry B. Wonham's article '"I Want a Real Coon": Mark Twain and Late-Nineteenth-Century Ethnic Caricature' (American Literature 72(1), March 2000, 117-52) contains interesting discussion of the complexities of Twain's use of ethic stereotypes. In addition to stereotypes fixed in fictional and cartoon sources, Wonham also refers to songs—including 'All Coons Look Alike to Me.'↩

8. Joseph Conrad, Heart of Darkness and Other Tales. Edited by Cedric Watts. World's Classics Edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002, 139.↩

9. Joseph Conrad, The Nigger of the 'Narcissus'. Edited by Allan Simmons. Everyman Centennial Edition. London: Dent, 1997, 94.↩

10. Joseph Conrad, An Outcast of the Islands. Edited by J.H. Stape. World's Classics Edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002, 229-230. This is Conrad's second novel, first published in 1896.↩

11. Joseph Conrad, Heart of Darkness and Other Tales, 50.↩

12. Joseph Conrad, Heart of Darkness and Other Tales, 117..↩

13. Joseph Conrad, Heart of Darkness and Other Tales, 9-10.↩

14. Joseph Conrad, Tales of Unrest. Dent Collected Edition. London: Dent, 1947, 66.↩

15 Joseph Conrad and Ford Madox Ford, The Inheritors. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Alan Sutton Publishing, 1991, 137.↩

16. Joseph Conrad, Nostromo: A Tale of the Seaboard. Edited by Keith Carabine. World's Classic's Edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1984, 100.↩

17. Joseph Conrad, Nostromo: A Tale of the Seaboard, 453; 459.↩

18. Joseph Conrad, Under Western Eyes. Edited by Jeremy Hawthorn. World's Classics Edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003, 181.↩

19. Joseph Conrad, Chance: A Tale in Two Parts. Edited by Martin Ray. World's Classics Edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988, 152-3.↩

20. Joseph Conrad, Chance: A Tale in Two Parts, 42.↩

21.Joseph Conrad, Victory: An Island Tale. Edited by Mara Kalnins. World's Classics Edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004, 292.↩

22. Joseph Conrad, The Nigger of the 'Narcissus', 13.↩

23. Joseph Conrad, Lord Jim. Oxford World's Classics Edition. Edited by Jacques Berthoud. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002, 175.↩

24. I have written more about the racism of The Nigger of the 'Narcissus' in a chapter in myJoseph Conrad: Narrative Technique and Ideological Commitment (London: Arnold, 1990).↩

Jeremy Hawthorn is Professor Emeritus of Modern British Literature at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim. He has published three monographs and a number of articles on the fiction of Joseph Conrad, and has edited Conrad’s Under Western Eyes and The Shadow-Line for Oxford World’s Classics. He co-edited a special issue of The Conradian on Conrad’s Under Western Eyes in 2011. Other publications include Cunning Passages: New Historicism, Cultural Materialism and Marxism in the Contemporary Literary Debate (1996), A Glossary of Contemporary Theory (4th edition 2000), and Studying the Novel (6th edition 2010). Recent articles have included ones on the concept of narrative occasion, and on the “Kai Lung” stories of Ernest Bramah. A monograph The Reader as Peeping Tom: Nonreciprocal Reading in Fiction and Film has been accepted for publication by Ohio State University Press. He is a member of the editorial board of the Cambridge Edition of the Works of Joseph Conrad and, with Max Saunders, is editing The Inheritors: An Extravagent Story and “The Nature of a Crime” for a volume in the Cambridge edition.

Jeremy Hawthorn is Professor Emeritus of Modern British Literature at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim. He has published three monographs and a number of articles on the fiction of Joseph Conrad, and has edited Conrad’s Under Western Eyes and The Shadow-Line for Oxford World’s Classics. He co-edited a special issue of The Conradian on Conrad’s Under Western Eyes in 2011. Other publications include Cunning Passages: New Historicism, Cultural Materialism and Marxism in the Contemporary Literary Debate (1996), A Glossary of Contemporary Theory (4th edition 2000), and Studying the Novel (6th edition 2010). Recent articles have included ones on the concept of narrative occasion, and on the “Kai Lung” stories of Ernest Bramah. A monograph The Reader as Peeping Tom: Nonreciprocal Reading in Fiction and Film has been accepted for publication by Ohio State University Press. He is a member of the editorial board of the Cambridge Edition of the Works of Joseph Conrad and, with Max Saunders, is editing The Inheritors: An Extravagent Story and “The Nature of a Crime” for a volume in the Cambridge edition.

Back to the start of the essay.